Look inside the Fred Elwell Book - plates excerpts

Here are a small selection of the 141 plates featured in Fred Elwell RA — A Life in Art. Each one is reproduced in full colour with a detailed description.

← Previous plate Next plate →

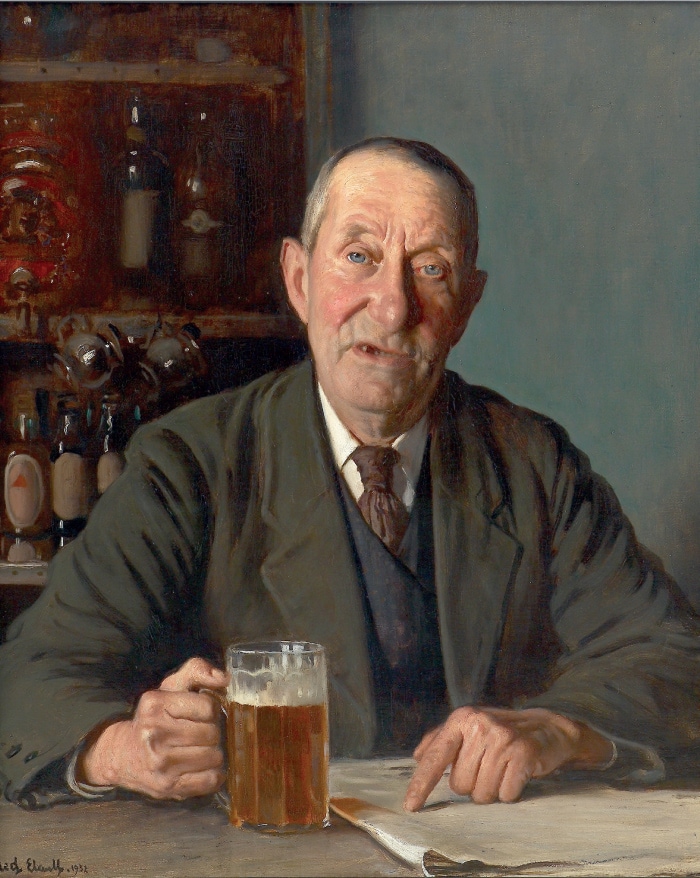

74Man with a Pint

- Oil on canvas

- 91.5 × 106.75 cm (36" x 42")

- Signed and dated 1932

- Grundy Art Gallery, Blackpool

- Exh. RA 1933

The man is grasping the beer-mug with an air of an habitué. Though he is an everyday kind of a fellow with orange-peel skin and a bulbous nose, Elwell gives him centre-stage. There is tension between our expectation of a figure more heroic and handsome, and the frank reality. The humour which this generates is entirely sympathetic.

The artist‘s own hostelry was the Rose & Crown in Beverley, where Elwell was a popular customer. The subject of beer at the time was a matter to be held up to the light. In the last budget the price of a pint had been raised by one penny.

The contemporary public enjoyed this painting’s human qualities. As The Artist stated, Elwell belongs to the School whose purpose is Life. To the modernist of the time such a concept was irrelevant, but “true art has no fashion” and artists like Elwell, to quote The Artist, will be seen to have “held art together during a time when insane ideas sought to prevail”.

With Life in the forefront, this drinking man represents it as he engages us in conversation as his fellow drinkers. He appears to make a point, stabbing the newspaper with his finger. The sense of a personal encounter makes his presence even more real.

At the Royal Academy summer exhibition in 1933 this striking piece was Picture of the Year, a true statement of its huge popularity.

47Performers’ Entrance

- Oil on canvas

- 50.75 × 66 cm (20" x 26")

- Signed

- East Riding of Yorkshire Council (Museums)

A performer clothed in exotic costume rides out of the deeply shadowed Big Top at Sanger’s Circus into the clear sunlight. His act is over, but others prepare to begin. “The romance of a big sagging tent”, and the presence of the Spanish girls, bullfighter, and leering clown were eagerly remarked upon when this work was exhibited in 1927 at Sunderland, at a time when, throughout the country, such performers were the champions of popular affection.

From its appearance the performer's entrance might almost be the stage itself. Elwell has seized upon this strange inversion, visually there is drama to be found outside the performance. Against the dark interior the figures are silhouetted and active. The swirling movement of a red cloak is described by its flowing line and uneven edge in the painting technique. Guy-ropes create a pathway that attracts the viewer into the scene.

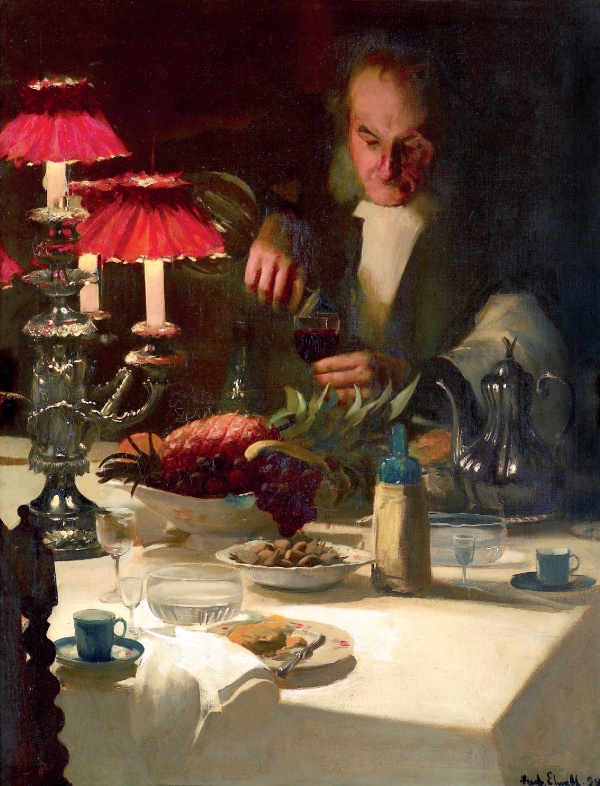

2The Butler takes a Glass of Port

- Oil on canvas

- 94 × 74 cm (37" x 29")

- Signed and dated 1890

- Beverley Art Gallery, East Riding of Yorkshire Council (Museums)

Earlier in the day this man discharged his duties in the proper manner, serving his master and guests at table. The same butler now emerges from the shadows of the room to take for himself a furtive glass of port – not for the first time we suppose (judging by his luminous nose!). The playful double-entendre on that word “takes” is associated with this very moment of relish painted by Elwell into the picture. The same may be said for the even better title of All Things come to the Man who Waits.

Indeed the butler’s shrewd expression, most readable in candle glow, shows he is well informed as to the warmth, quality and glorious nectar to be imbued. As he savours it in anticipation, we perceive Elwell’s extraordinary ability to convey those feelings to us.

Such dramatic use of light was not uncommon among early Netherlandish artists, such as the Utrecht Mannerists. A leading proponent of the style, Gerard Seaghers (1591-1651), shows how skilful and effective this method can be. We consider that Elwell equals this.

126Léonie Reading

- Oil on canvas board

- 45 × 37.5 cm (18" x 15")

- Private collection

This Parisian portrait of Léonie reading a book must be one of the most delightful that Fred Elwell accomplished. It conveys his deep affection. Having chanced upon her in this simple pose, silently in a moment of magic, he feels impelled to paint her quickly.

Seemingly intertwined are the chair, figure and the standard lamp by which she reads. It is a unity of composition, a central focus. Nothing else is there, nor needs to be.

The picture is painted at speed, using fluid strokes with a heavily loaded brush, especially in the representation of her arm caught in a band of light. The glorious orange-golden yellow emanating from the shade diffuses the whole picture with tranquillity, softness and warmth.

A connoisseur of the French Impressionists, on first sight of this picture, saw it as an example of French Impressionism to perfection, “I should recognise it. Enlighten me”, he insisted.

108Léonie’s Toilet or Dolls

- Oil on canvas

- 75 × 62.25 cm (49½" x 28")

- Signed and dated 1894

- East Riding of Yorkshire Council (Museums) Exh. RA 1935

The model Léonie was introduced to Fred Elwell on his arrival in Paris by his Lincoln friend Tom Warrener. When Tom painted her, he used the longer stage-name of Léonline. This painting of Léonie’s Toilet announces that Elwell was not only sharing Warrener’s model but also the artistic scene his friend inhabited. This particular choice of subject recalls Seurat‘s then contemporary painting of the Young Woman Powdering Herself, and that was exhibited at the Société des Artistes Indépendants when Elwell first came to Paris in 1892. To represent a woman at her toilet was becoming a modern subject. Degas painted The Tub, for instance. Elwell’s Léonie is similarly self-absorbed as she powders her face. Alone within her own ambience, she is unaware of being observed.

The painting also displays Elwell’s surprising involvement in French contemporary life. A copy of the day‘s issue of the gossipy newspaper Gil Blas is draped over the washstand, and Japanese dolls, which were currently in vogue, hang from the mirror. Again, Elwell is truly alive to aspects of abstract and modern formal principles. See how Léonie‘s left arm parallels the mirror edge; the doll opposite echoes her own form yet in reverse; and everywhere can be spotted those shapes which somehow and interestingly overlap and inter-relate.

Yet the painting is also witness to his training at the Julian under the academic William-Adolf Bouguereau. In this context, he would be expected to portray the nude from a life model, employing subtle gradations of tone for the pearly tints of her flesh, and this he does. Sibylle Cole, writing on this subject, points out the fine range of whites and lovely soft edges where “the light leaks into the background”, in a manner which relies more on tonal values than colour. Elwell was inspired by both academic and modernist elements simultaneously, but it was the alignment in general terms with the academic camp that most assisted him in his submissions to the Paris Salon, and even more to the Royal Academy London where this was exhibited in 1895.

Despite the foregoing, Elwell had been obliged to part with the Léonie picture in payment of rent for his Paris accommodation; and she was discovered only when a fellow royal academician, James Bateman, some 50 years later, espied her on display in an antiques shop in King’s Road, Chelsea. He gladly bought the painting and returned it to the now elderly Elwell, who was delighted to become re-acquainted with this early work. He nostalgically said that it rang “a whole peal of bells” in his memory.

He refused emphatically to part with her again, and when Elwell exhibited the picture for a second time at the Royal Academy, The [Hull] Daily Mail reported how Academicians were talking with unusual enthusiasm about one picture, as well as seeing the veteran artist in a somewhat different light. Elwell himself was still quietly fixated on Léonie’s “lovely, exquisite feet”!

116Conversation Piece

- Oil on panel

- 27.5 x 37.5 cm (11" × 15")

- Private Collection

This painterly study of a convergence of three people in the drawing room of Bar House is the very essence of a conversation piece. Figures are grouped rather as Vanessa Bell’s painting of the same name; they centrally merge and meet. Yet in this piece by Elwell their form constructs a web of intrigue. The body language appears to create an emotional distance, each elegant figure elongated towards the centre base, accentuating this strangeness.

Even the legs of the drop-leaf table join this enigmatic convergence. The fluidity of brushstrokes seems to recall Elwell’s painting of Léonie Reading (Pl.126) in terms of its style; expressively Parisian in influence. Equally comparable is the quality of lamplight which imparts a glorious glow within the room. In Conversation Piece this luminescence highlights the exquisite standing figure who is dressed in diaphanous yellow against more yellow. We believe the man to be Alfred Munnings whose practice was to stay at Bar House for Beverley race days. His wife is seated opposite him in the room. The ethereal third figure in the centre has been compared with a similar portrait by Alexander Forbes, of Florence Carter-Wood, Alfred’s tragic first wife who died by her own hand at Lamorna.

It is speculative, of course, but we wonder if this third person may be a reason for the painting being secreted in the Elwell safe for 25 years. Could she be a vision from the past of a dearly loved friend, of whom her husband never spoke again? Much later, the picture was discovered, together with A Hidden Corner (Pl.36), a view of Bar House by Mary Dawson Elwell. This was perhaps her last, before the disabling stroke that ended her career. Again, that painting only saw light of day after the safe was opened.

30Beverley Minster from the Friary – by Mary Dawson Elwell

- Oil on canvas

- 61.9 x 74.2 cm (24½" × 29¼")

- Signed and dated 1923 (or 8)

- East Riding of Yorkshire Council (Museums) Exh. RA 1934

Beverley Minster is shown by Mary in the light of modest houses which surround it from the south-east. The mighty edifice of the Minster appears without pomposity and in harmony with the many small urban gardens.

The church is viewed in its most human aspect, united in mood with the town it serves. Bold accents of colour animate the scene. The serried line of gates leads endearingly towards the hazy slate roof of the church. Reddish shades of old brick resonate against the green of homely garden gates and the colourful patchwork of washing as it freely billows.

The painting is alive with local details of its period. Not least is the evidence of some women taking in washing for other people in the town. Miss Woodmansey managed this business in her wash-house with only a gas ring for heating the water. Washing was hung to dry in her garden every day except Sundays. She and others occupied the three dwellings of the Friary (its gable end visible on the right).